Polymicrobial disease: Redefining how infections are understood and treated

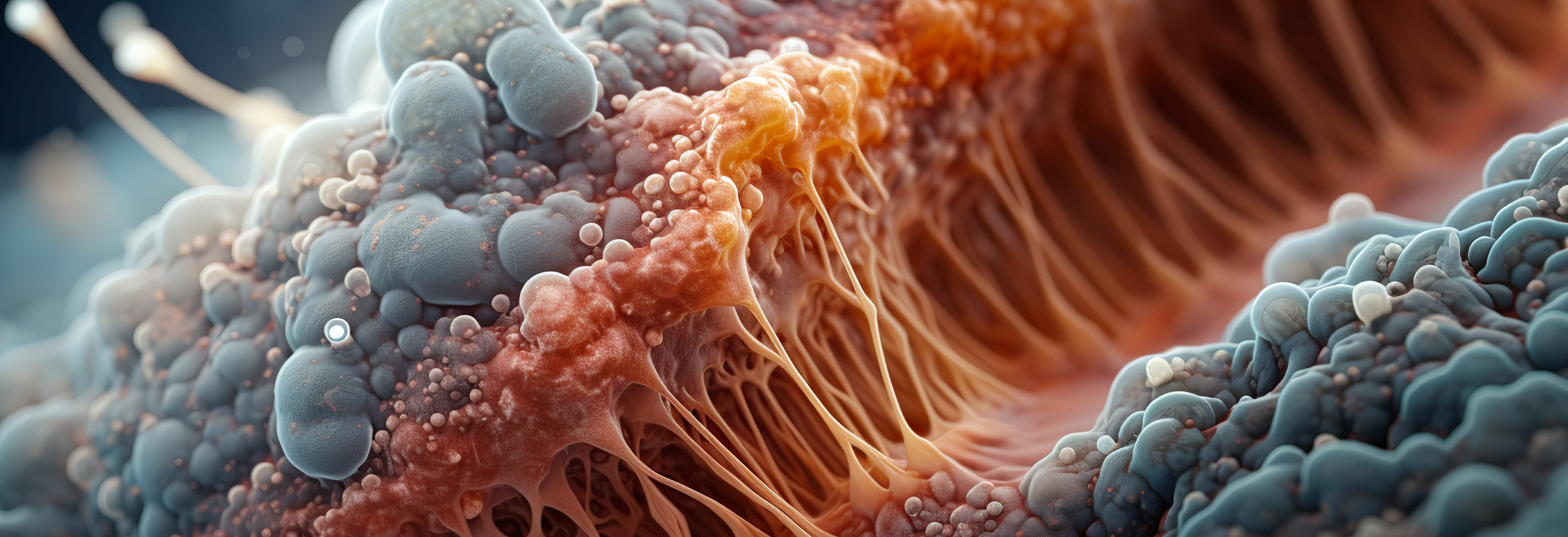

Many of the most persistent and clinically challenging infections are not caused by a single pathogen, but by complex communities of microorganisms that coexist, interact, and adapt within the host. These polymicrobial infections underpin chronic wounds, respiratory disease, otitis media, sinusitis, and device-associated infections, and they are a major driver of antimicrobial treatment failure worldwide. Despite this reality, most current therapies, diagnostics, and regulatory frameworks remain built around a single-pathogen view of disease. This mismatch between biological complexity and clinical practice has contributed directly to recurrent infections, prolonged inflammation, and the accelerating global crisis of antimicrobial resistance.

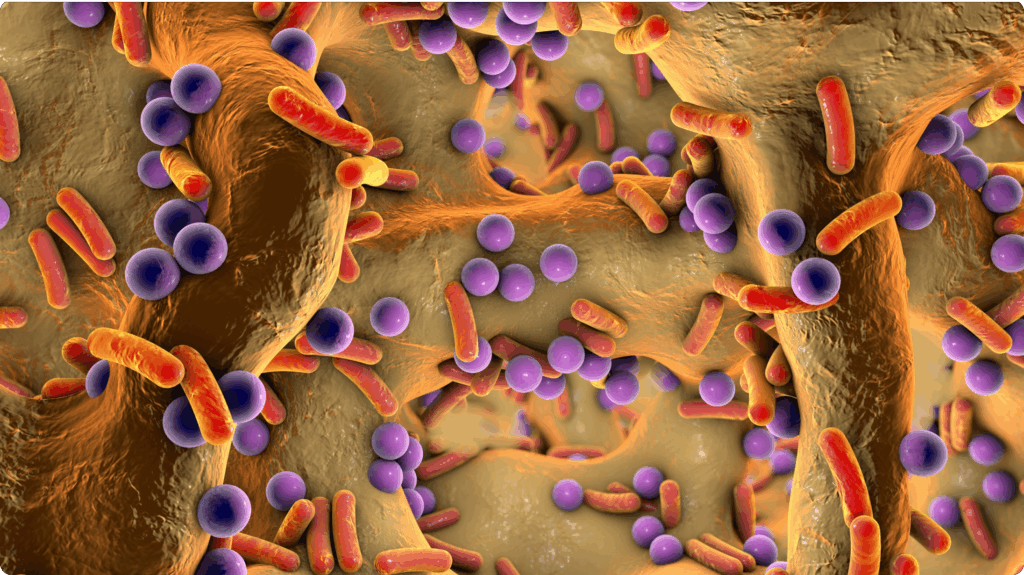

Research over the past decade has made it increasingly clear that pathogens behave very differently in polymicrobial communities than they do in isolation. Interactions between microbes can profoundly alter virulence, metabolism, and antibiotic susceptibility, often enabling pathogens to persist despite aggressive treatment. Within these communities, bacteria communicate, share resources, compete for space, and exploit host immune responses in ways that cannot be predicted from monoculture studies. As a result, antibiotics that perform well in standard laboratory assays frequently fail when applied to real-world infections, where biofilms, spatial organisation, and host-derived stresses dominate microbial behaviour.

This arm of our research directly addresses this gap by placing polymicrobial interactions at the centre of infection biology and therapeutic development. Rather than simplifying infections to single organisms, it embraces biological complexity as a source of insight and opportunity. By developing and applying clinically relevant polymicrobial infection models, the project captures the emergent properties of microbial communities that drive chronicity, tolerance, and treatment failure. These models allow for the integrated, biologically meaningful study of infection dynamics, host responses, and therapeutic outcomes.

A central aim of the project is to uncover the mechanisms that govern microbial cooperation and competition during co-infection. When pathogens coexist, they frequently activate pathways that are dispensable in isolation but essential for survival in a shared environment. Identifying these conditionally important processes creates entirely new opportunities for intervention. By combining advanced genetic approaches with realistic infection models, the project reveals vulnerabilities that emerge only in polymicrobial settings—targets invisible to traditional drug discovery pipelines.

The project also provides a rigorous framework for evaluating antimicrobial therapies under conditions that reflect clinical reality. Antimicrobials, drug combinations, and biomaterial-based delivery systems are tested against polymicrobial infections rather than simplified monocultures, ensuring that efficacy is assessed in the context where failure most often occurs. This approach improves translational relevance and reduces the risk that promising therapies will fail late in development due to unanticipated community-level effects.

Beyond its scientific contributions, the project has broad implications for healthcare and public health. Improving our ability to predict treatment outcomes in complex infections supports more effective and durable therapies, reduces recurrence, and limits the selective pressures that drive antimicrobial resistance. The knowledge generated will inform clinical decision-making, guide future therapeutic development, and contribute to more equitable health outcomes for populations disproportionately affected by chronic infectious disease.

Ultimately, this project challenges a long-standing assumption in infectious disease research—that pathogens can be understood, targeted, and eradicated in isolation. It demonstrates that infections are ecological systems, shaped by microbial interactions and host responses, and that successful treatment must account for this complexity. By redefining how infections are studied and treated, the project lays the groundwork for a new generation of antimicrobial strategies designed for the realities of polymicrobial disease.

Further reading

- Wardell SJT, Yung DBY, Nielsen JE, Lamichhane R, Sørensen K, Molchanova N, Herlan C, Lin JS, Bräse S, Wise LM, Barron AE, Pletzer D. A biofilm-targeting lipo-peptoid to treat Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus co-infections. Biofilm. 2025 Mar 12;9:100272. doi: 10.1016/j.bioflm.2025.100272.

- Wardell SJT, Yung DBY, Gupta A, Bostina M, Overhage J, Hancock REW, Pletzer D. DJK-5, an anti-biofilm peptide, increases Staphylococcus aureus sensitivity to colistin killing in co-biofilms with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2025 Jan 8;11(1):8. doi: 10.1038/s41522-024-00637-y .

- Yung DBY, Sircombe KJ, Pletzer D. Friends or enemies? The complicated relationship between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2021 Jul;116(1):1-15. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14699.